- Home

- Diana Giovinazzo

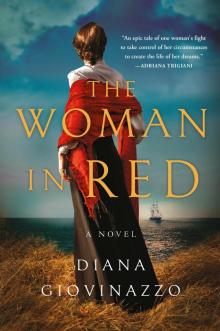

The Woman in Red

The Woman in Red Read online

This book is a work of historical fiction. In order to give a sense of the times, some names or real people or places have been included in the book. However, the events depicted in this book are imaginary, and the names of nonhistorical persons or events are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance of such nonhistorical persons or events to actual ones is purely coincidental.

Copyright © 2020 by Diana Giovinazzo Tierney

Cover design by Evan Gaffney. Photograph of sky: Evgueni Zverev / Alamy Stock Photo; photograph of woman: Rekha Arcangel; photograph of ship and ocean: © Mark Owen / Trevillion Images. Cover copyright © 2020 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights.

Grand Central Publishing

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

grandcentralpublishing.com

twitter.com/grandcentralpub

First Edition: August 2020

Grand Central Publishing is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Grand Central Publishing name and logo is a trademark of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Giovinazzo, Diana, author.

Title: The woman in red / Diana Giovinazzo.

Description: First edition. | New York : Grand Central Publishing, 2020.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019049247 | ISBN 9781538717417 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781538717424 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Garibaldi, Anita, 1821?–1849—Fiction. | Garibaldi, Giuseppe, 1807–1882—Fiction. | GSAFD: Biographical fiction.

Classification: LCC PS3607.I4686 W66 2020 | DDC 813/.6—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019049247

ISBNs: 978-1-5387-1741-7 (hardcover), 978-1-5387-1742-4 (ebook)

E3-20200630-DA-NF-ORI

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Epigraph

Prologue

Part One One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Part Two Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Part Three Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven

Twenty-Eight

Twenty-Nine

Thirty

Thirty-One

Thirty-Two

Thirty-Three

Thirty-Four

Thirty-Five

Thirty-Six

Thirty-Seven

Thirty-Eight

Thirty-Nine

Forty

Forty-One

Forty-Two

Part Four Forty-Three

Forty-Four

Forty-Five

Forty-Six

Forty-Seven

Forty-Eight

Forty-Nine

Fifty

Fifty-One

Fifty-Two

Fifty-Three

Epilogue

Author’s Note

Acknowledgments

Discover More

About the Author

Reading Group Guide

Explore book giveaways, sneak peeks, deals, and more.

Tap here to learn more.

Destiny toys with us with both hands. For my sins, I will pay, as all of us must. More, I think. But I still rejoice in the family she brought me.

—Anita Garibaldi

Prologue

August 1840

Bad omens have followed me all my life. I was born in an unlucky month, under an unlucky moon. “August, the month of sorrow and grief.” It is a saying I know all too well, and it haunts me now as I pick my way through the soulless bodies on a deserted battlefield in the middle of the Brazilian wilderness.

A low fog flows through the field, covering the ground with a thin mist. It’s not enough to hide the carnage. These men, strewn about like broken china, were people I knew. They shared a campfire with my husband, hanging on his every word, just as I did once upon a time. So many men. I clasp my belly and say a silent prayer for my child as I wonder what will become of us. This battlefield that may have claimed my husband spreads out before me.

I look back at my captors, playing cards by the lantern light. Young men in tattered uniforms with unshaven faces. One of them slaps down a card and cheers as they continue to play. They want to leave, but I made a deal with the devil to be here. None of us can go until I am satisfied. These young soldiers underestimate me, just like so many others.

Slumping against a fallen tree, I rub my pregnant belly as I watch black vultures circle and swoop in a golden-red sky. My chest heaves with exertion as the stench sticks to the back of my throat, sweet and rancid. It threatens to overtake me, but I must continue. I have been here for hours, searching and wondering if these birds might be an omen. Is my husband dead?

I close my eyes at the childhood memory of a hunched old woman shaking her knobby fingers at me from the steps of the church as she proclaims, “This one, she will have a hard life. So very, very unlucky, this one,” before spitting off to the side, to ward off the devil.

But her proclamations made no difference. My mother already knew I was unlucky. I wasn’t born a boy. My life could have been infinitely different if I had been. Perhaps I would be one of the bodies scattered here among the mud and filth.

A branch cracks and I startle at the sight of a vulture walking in front of me. He dips his head down and pulls the flesh from a soldier, then turns to look at me as he gulps his meat. His black eyes shine in the dying light. We regard each other, this scavenger and I, and in him I recognize a creature not unlike myself. We do what we must to survive. The vulture flaps his massive wings and is gone.

My stomach churns and bile sets my throat on fire. Doubling over, I try to expel the acid, but nothing comes. I wish I had some water, anything to get the bitterness out of my mouth. Wiping my damp hair from my face, I look around me at the muddy field. My back seizes as I push myself up. Gasping against the pain, I catch an abandoned wagon before I fall face-first into another dead body. I close my eyes and try to control my breathing as I fight against the hopelessness that is setting in. This field is large and our losses enormous; there is no way that I can search through it in one evening.

My husband can’t be here. Men like him don’t die. He is too cunning. But in the back of my mind I can’t help but wonder what it means for me if he is. There are so many men, it’s not impossible to think that what they told me was true.

I turn back to the tree line as I realize, I could run. I could leave this place

. I could sneak away from these incompetent idiotas. I could become something greater than my husband. They would whisper the name Anita Garibaldi in reverence.

Closing my eyes, I step forward, my boots sinking ever so slightly in the mud. Memories rush past me as I make my way across the field. Only time will tell if I am making the right decision.

Part One

Santa Catarina, Brazil

One

October 1829

I was eight years old when I was sent to school in the small trading settlement of Tubarão. But conforming was never my strong suit. I tried my best to be like my two older sisters, my hair in braids, my dress freshly pressed, but I couldn’t sit still and pay attention. Our one-room schoolhouse was small and stale. I could feel the thick, hot air in my lungs making me struggle for breath.

This was once the justice of the peace’s office, but the villagers’ children needed a place to learn to read. He got a new building and we got the old one, yellowed with age and adorned with thick cracks that climbed the walls. Everyone was happy.

We sat at our desks, four rows across, every child dutifully listening to the basic lessons that would allow us to take over our parents’ roles in the village one day. The teacher droned on, reading from a book.

Sighing, I looked out the window to where a cherry guava tree grew. One of the branches, thick with bright pink berries, bounced up and down in the morning sun. I leaned out of my chair to get a better look at what was making such a ruckus. The little black nose of a wild coati poked through the lush green leaves. I watched as the little creature carefully walked out to the edge of the branch, seeking out the ripe guava.

“Anna de Jesus! Get back in your seat!” the teacher yelled, snapping my attention back to him.

“But, senhor—”

He grabbed me by the arm to pull me in front of the class and made me hold out my hands. I tried to rip them away, but it only caused his grip to tighten. He slapped them firmly with his ruler. The sting resonated up my forearms into my elbows. “Do not speak back to your teacher. You are a girl. You should obey.”

Hot tears stung my eyes. I wasn’t going to reward him; I bit the inside of my lip to keep from crying out. Blinking back the tears, I could feel the other students’ eyes on me. It wasn’t until a giggle rippled up from the back of the room that my embarrassment led to anger. I grabbed the ruler from his hand and started to hit him with it. I could see nothing but my hand gripping the ruler as it made contact with my teacher’s arms, raised in defense. It was the last time I ever went to school.

“What are we going to do with you, Anna?” my mother asked, red-faced, nostrils flaring like a bull’s. We were in the safety of our small home with its thatched roof and mud-and-straw walls, away from the prying eyes of the village. My mother was always careful with what ammunition she gave the town gossips. I sat at the table, looking up at her, fear making my stomach clench.

“She will come to work with me.” Neither my mother nor I had heard my father come in. He was standing in the doorway, wiping a damp rag under his chin and ears. Mamãe straightened her back as she eyed my father.

“You are too soft on her. This,” she said, pointing to me, “this is all your fault.”

“This is our daughter. We could use the extra hands with the horses.” He looked down at me with his arms crossed, the hint of a smile on his face. I tried not to meet his smile.

My mother threw her arms up in the air as she walked in the opposite direction from my father. “I give up!”

I grinned broadly at her back as she stormed away. My father’s face grew stern as he regarded me. “Wipe that smile off your face. This will be hard work.” I nodded in agreement as he stalked off.

Working alongside my father with the horses and cattle was wonderful. Our area of southern Brazil, known as Santa Catarina, was a true Eden. No one loved the wild, rugged country like the gauchos, and Brazil couldn’t function without us.

We spent our days taming the wild land of Santa Catarina. Every year more people settled here from Europe and northern Brazil, requiring more land, more cows, and more resources in general. When a rancher lost one of his cattle, it was my father and the other gauchos who went out to find it.

Santa Catarina would not be the country that it was without the gaucho, and the gaucho would not be the gaucho without Santa Catarina. We worked under a wealthy landowner, who was referred to as a patron. A patron would not think of muddying their boots to drive a herd of cattle from one clearing to the next. A patron would not rise with the sun to feed the horses and cattle that made them wealthy. A patron would not leave the warmth of their bed in the middle of the night to help a cow give birth to a calf, not caring about the blood and mucus that came with. But a gaucho would. We didn’t need noble titles to know that we were the true owners of this land, with its lush green mountains that languidly stretched to the heavens. A wilderness that opened before us like the expanse of the ocean was better than any heaven promised to us by priests.

I was at my happiest when I rode out with these dirty, unkempt men who braved the wilds, through the downpour that attempted to cleanse all living things from the earth. No, I did not envy my sisters and former classmates. While they stayed in the airless classroom listening to a useless lecture, I was getting a real education.

Working as my father’s apprentice at first, I lined up his tools, making sure they were all in working order for him. I quickly became experienced enough to work alongside him, a full gaucho in my own right. At the end of the day, we cleaned the tools together, talking. My father told me stories about his people, the Azoreans who resided on the lush, exotic islands off the coast of Portugal.

“When I was a child, my parents couldn’t keep me on the ground.” He smiled as he wiped the mud off his prized facón, the knife that he had kept by his side since he first moved here. “There was this one bluff in particular that my friends and I liked to climb. It was so high that you could see for miles over the ocean.” He put the facón away and picked up another tool as I sat on the stool watching him. “When you stand on a bluff like that, you understand just how small you are.”

“What did you do after you reached the top?”

“We jumped.” His eyes got big as he tickled me. “But don’t you go getting any ideas now, little lady. I will not have you jumping off cliffs until you are at least…twenty.”

“Twenty? Why twenty?”

“Because by then you will be your husband’s problem.”

I wrinkled my nose at the thought, but then another question struck me. “Papai, why did you come here?”

He thought for a moment as he closed the toolboxes. After a while, he finally answered, “I understood there was more to the world than my little island.”

Two

January 1833

As ran the course of my life, the omens came, and with them came trouble.

One morning while my father and I were preparing for our day’s labor we heard my mother call out from the house. We dropped the tools that we had been packing and ran to her side. She was standing in the kitchen, staring at a little black bird with a bright red belly, sitting on the back of a chair, his little head rhythmically bobbing up and down.

“This is bad. Very bad.” My mother crossed herself as the color left her face. “There are spirits here.” She crossed herself again. “Something terrible is going to happen.”

I slowly walked up to the bird so that I didn’t startle him, setting one foot cautiously in front of the other. The bird turned his little head toward me. His eyes, as black as his feathers, shone brightly under his white-streaked brows. Gingerly I reached out toward him, stroking his little chest. The bird didn’t move or flinch. Our eyes met and for a moment I felt a kinship with this creature. Moving slowly, I scooped him up in my hands and carried him outside, where I released him back to the wild where he belonged.

It was a hot January day when my father volunteered to figure out where the leak was coming

from in the community storeroom, where our small village’s produce and dried meats were stored during the rainy season. Any amount of moisture in that hut and we would all be starving for the rest of the season.

I volunteered to go with him, but he wouldn’t let me. “You’re too small. You might get hurt.”

“Just last month I helped catch a wild bull.”

“And you nearly got yourself trampled.” He gathered his rope and hammer. “You are eleven years old. You will have plenty of time to risk your life chasing cattle and climbing on top of rickety sheds.” He kissed the top of my head and left. I sulked, wishing I could go with him. They may have let me help rope the bull, but it was only because I was quicker with the lasso than the rest of the gauchos we rode out with.

Later that morning I was out at the stables, grooming the horses, when the news swept in like a rushing storm destroying everything in its path. The whole village went running to see the damage to the storeroom. Bile rose in my throat as I began pushing forward.

“He was walking on the roof,” one of my neighbors murmured. “They say he fell.”

“Of course he fell; that roof was so brittle that I don’t think it could even support the weight of a bird.” Their words died on their lips as they looked down, noticing me for the first time.

Weaving through the crowd that gathered, I made my way to the center of the room. It was only when I gasped at the sight—my father, white and waxen as he lay impaled by a beam through the abdomen—that I think I screamed. I couldn’t tell. Lurching forward, I tried to grasp his outstretched hand. That’s when one of the gauchos grabbed me. He threw me over his shoulder and carried me out the door.

The next day family, friends, and other kin gathered for the processional to bury my father. They hollered and cried, thumping their chests and pulling at their hair. My mother led the group, the loudest mourner of all. When the horse-drawn carriage came to a stop, she threw herself over the coffin, beating the lid as she exclaimed, “How could you leave me?” Two women pulled her away, her wails a low fog rising above the crowd of mourners.

The Woman in Red

The Woman in Red