- Home

- Diana Giovinazzo

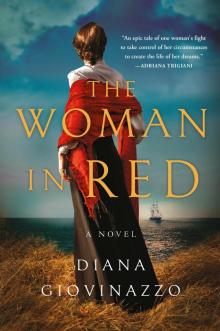

The Woman in Red Page 2

The Woman in Red Read online

Page 2

I stood in the back, watching the spectacle that played out before me. People crowded around me as the whole village pushed past me to follow the casket. Clinging to a tree, I did my best not to get swept away by the current of faces that moved toward the graveyard. Looking around, I could no longer see my mother or my sisters. Suddenly, I felt alone and scared in this sea of people.

Their noise was a cacophony that made me feel disoriented. Their sweat clung to my nostrils as I was jostled along the pathway. I had to leave. I was feeling myself go mad. Fighting through the procession, I made it to the river, my pulsing lungs on fire, and collapsed by a tree, gasping for breath. This world suddenly felt cold and dark without my father. He was the only one who understood me.

That was when I heard the footsteps behind me. I turned my head sharply, expecting it to be a wild animal, only to see Pedro, the village drunk. He smiled; half of his teeth were missing, and I could see his tongue in the gaps.

“Such a little thing. So sad that you are all alone now.”

“Go away, Pedro,” I said, looking back at the river but keeping watch on him from the corner of my eye.

He swaggered over to me and took one of my braids in his hand. “Such pretty long hair you have.” He let the braid slip through his dirty fingers. “Such a shame that you don’t have a father to protect you anymore.”

“Leave me alone, Pedro.” I went to move away but he grabbed me by the arm, throwing me against a tree.

“You do not speak to men that way.” He was so close I could smell his cologne of alcohol and urine. “I should teach you a lesson.” He pressed me up against the tree as he fumbled with his pants.

I began to struggle. He pinned me harder, licking my cheek. “Be a good girl.” His words were thick and wet.

Instinct kicked in and I stopped struggling. I went limp, slipping through his clutches, and ran faster than I had ever run in my life back to our house.

Most of the guests were gone by that point, but my mother was just outside our front door, having said goodbye to someone. I ran to her and wrapped my arms around her, feeling safe in her strong embrace.

“Anna, what has gotten into you?”

I buried my head in her neck, unable to bring myself to speak. When I finally did, I told her everything. Her face went from pale white to crimson. “That louse. You are lucky you were able to get away.” She held my head in her hands in order to look into my eyes. “You have to be careful. We no longer have your father here to protect us.”

That night I lay in my bed with my older sister Maria snoring beside me. It felt like there was a chasm between us. Even though we were only three years apart, she acted as if she were one of the adults. We had never been close, but the ways we expressed our shared grief for our father felt like night and day. Where I felt stripped bare, she turned inward. Maria wanted to be left alone to the point that she would sneer whenever I came around. Now, as I lay beside her, I couldn’t sleep, the events of the day racing through my mind. I stared at our thatched ceiling. Maria snorted and rolled over. I couldn’t help but think, Why do we need a man to protect us? I worked alongside the men, doing the same work that they did. I could ride a horse better than most of the men of our village. I was given the most stubborn horses to break. My father was the one who taught me. The day that he had discovered that I had a natural affinity for horses was one of the best days of my childhood. And perhaps the most stressful for him.

I could taste the hay and horse sweat that the hot November air had carried through our encampment. The horse shook her black mane every few minutes. Her eyes were wild, darting from person to person, her breath loud and heavy with her anxiety. Whenever one of the men tried to approach her, she would rear up, kicking out in an attempt to defend herself against their whips. I stood next to my father, who sighed heavily. “That is not how you break a horse.” My father had his methods, and this wasn’t one of them.

When the men were preoccupied with their siesta, and taking a break from the horse, I approached the pen slowly, holding out my shirt like a basket in order to carry all the figs that I had collected. She stood there regarding me; with every step I took she stomped her hoof and let out an angry whine. I stood by the fence and watched her as I put one of the soft fruits to my mouth.

The horse stomped in protest again. So I turned my back to her and continued to eat. It took only a few moments for her to come to me. She nudged my shoulder with her muzzle. When I didn’t respond, she nudged me harder, pushing me forward. I turned to look at her. We stared at each other until she quickly dipped her head. I smiled, holding one of the figs out in the palm of my hand. It was gone in an instant. Then another. Before I gave her a third she had to let me pet her. She shied away at first but by her seventh and last fig, her head was in my hands, letting me rub her as she sniffed for more food. At the sound of a cracking twig, she ran away, making laps around the pen. I turned to find all of the men, including my father, watching me. An old man leaned in toward my father, whispering something. My father grimly nodded and strode over to me. “It’s time for you to get in there with her.”

I had watched him break a horse a hundred times, horrified at the prospect of doing it myself. He nodded toward the horse as she nervously trotted around the pen.

“She’s going to try to break you more than you are going to try to break her,” my father explained. “Do not let her know she has scared you.” The horse’s ears were back as her large nostrils flared, releasing angry huffs. My father paused, staring down at the horse. “And for the love of God, don’t turn your back to her.”

Hesitantly I climbed over the faded wooden fence and stood there watching her. She shook her head, letting out angry huffs and snorts. Then she charged me. I stood my ground as she came barreling toward me, just like I had seen the men do. And at the last minute, she broke off, running the perimeter of the fence. I breathed a sigh of relief as I readied myself for her next attack. This dance between gaucho and horse was one I had seen many times. We continued like this for most of the afternoon, until she stopped, panting and huffing. She stomped her hoof into the dirt like an angry child. I made shushing noises as I approached her. Slowly I reached out a hand and stroked her sides. I was patient as I worked the rope around her. She trusted me and I wasn’t going to violate that trust. I was my father’s daughter.

Now as I lay beside Maria, I wondered if I would ever be trusted to work like that again. I could rope a calf in ten seconds, the fastest in the village. Was I not as good as the gauchos because I was a woman? I certainly did not feel that way. Why should I be treated any differently now that I no longer had a father to watch over me? I punched my pillow and rolled over. I needed to do something. That’s when I decided that the next day, I would be the one to teach Pedro a lesson.

I spied the louse the next morning from a distance as he was doing his job, if you could call it that. He was a lazy farmhand who worked only if his boss was watching. He sat in the shade of a decrepit old pine tree, too focused on his drink to care about the oxen that were tied to the trunk with a thick rope. Years of termite damage made the pine slouch to the side like an old man in need of a cane. This was going to be too easy.

I kicked my horse in the hindquarters and she took off at a run straight for the oxen, who at this point noticed us. Their beady eyes grew large as they stopped chewing. The oxen pulled, trying to run away, bringing the tree with them, roots and all. Pedro, seeing this and seeing me, came right into my path with his arms raised in an attempt to stop me. He was just where I wanted him. I reached back and struck him with my whip, as hard as I could across his face. He cried out as if I had chopped off a limb. Blood seeped through his fingers and down his arm.

“Father or no father, you do not get to touch me.” I turned my horse and galloped away.

A few hours later the constable showed up at my door. He brought my mother and me to the justice of the peace, Senhor Dominguez, to discuss my incident with Pedro. Senhor Dominguez wa

s known as a fair man, but I didn’t know if I could trust him. He was short and bald with a little black mustache that made him look official. My mother and I sat stiff-backed in our chairs on the other side of the desk. The air was thick and hot even though his windows were open.

“I understand that you attacked Pedro this afternoon and damaged a very old tree.” He looked down his nose at me. “Do you want to tell me what happened?”

I stared at the dark spot on the wall above his head. He looked over at my mother, who shrugged. “I wasn’t there but I am sure that totó got what he deserved.”

He shook his head. “Luckily for you Pedro’s reputation precedes him. I suppose you have to protect yourself somehow.” He shuffled the papers on his desk. “Your father was a good man. I always enjoyed our talks. Just do me a favor and next time you try to teach someone a lesson, please don’t make such a mess. We’re still cleaning up after the oxen.”

When we arrived home, my mother made the decision: We were moving eighteen miles away, to Laguna at the coast, to be closer to my godfather. We would be safer there.

Three

June 1835

I hated Laguna. The city was a crowded jungle of houses that ran along the horseshoe bay. I could feel the heat that radiated off the homes painted in bright hues of blue, green, and yellow. The only things the houses had in common were the clay roofs that were baked into a deep red from the Brazilian sun. The people always yelled, one voice over the other trying to make itself heard.

Though every village had its gossips, Laguna’s were malicious. I was a favorite subject for them. How can a fourteen-year-old girl with no father walk the streets with such pride? Women whispered as I walked past them, their hands discreetly over their mouths, pretending they didn’t want me to hear. She doesn’t talk to anyone; maybe there is something wrong with her?

Wandering through the streets, I tilted my head to the heavens, praying to God to deliver me from such a wretched place. I missed my horse and our early morning rides. The smell of the woods after a rain. My freedom.

In a city so full of people, I was amazed to feel so…alone. My sisters, Maria and Felicidad, had been married off shortly before our move. I was left alone with our mother and our godfather, a shipping clerk. My mother took work cleaning the homes of the wealthy.

I ran my hands along my waist, feeling my hips, which had spread due to my newfound womanhood. My angular lines had softened out, giving me what many called a pleasantly plump profile.

One day as I was filling up the water jugs, I noticed a group of the village women talking in hushed tones, looking over at me in turn. When they saw that I was watching them they sauntered over to me, their baskets resting on their hips.

“It won’t take you very long to find a husband.” The lead woman wiggled her eyebrows as an amused smirk slowly spread across her face. “At least not with birthing hips like those.”

A petite black woman placed her hands on my hips, sizing me up. “Menina, if my hips were as wide as yours, I probably could have gotten a better husband. I certainly wouldn’t have had a twelve-hour labor for my last child.”

I tried to pick up my water jugs, but my arm hit my left breast, making me spill water everywhere. I could not get used to these things. They were suddenly always in my way. The women doubled over in laughter. “See, Gloria, I told you some women have all the luck.”

My new body was the talk of the gossips. Unfortunately, all of this led to men following me around asking to help with the most ridiculous things. As if I were unable to do anything for myself. They really were such a bother.

One morning, as the light from the rising sun crawled across the city, a sniveling, sorry excuse for a man by the name of Manoel Duarte approached me. Short and squat, at full height he barely stood above my shoulder. He looked as if he had just finished crying; his eyes were red, and he sniffled uncontrollably. If I didn’t know any better, I would think that he washed his hair with grease.

“May I carry your water for you?” he asked, out of breath from having to take large strides to keep up with me. I picked up my pace as he trailed behind me.

The next day he showed up at the well again. He asked if he could carry my water, and again I walked past him without saying a word. Surely if I continued to ignore him, he would go away like the stray dog that he was.

A few weeks later, while the sun set over Laguna, I sat down for our meager dinner of rice and beans with my godfather and mother. “I received a letter from your sister, Maria, today,” my mother said with a grin. “She is very happy with her husband. Ship caulkers make a fine living. She doesn’t need to work. Only tend to the house.”

“Good for her,” I said, reaching for more rice.

“I understand shoemakers make a good living as well,” my mother said. “One, in particular, seems to have his eyes on you.”

I looked up, stopping midchew. “Who?”

“A certain young man who likes to walk home with you from the well.” My mother smiled coyly as my godfather stared intently into his beans.

“Mother, I don’t know what you are talking about. There is only one person who likes…Oh no, Mother, you didn’t. Please tell me you didn’t.”

“I was paid a visit today by Manoel. He is a nice young man. He says that you and he—”

“He and I nothing!” I roared. “I have no interest in that man at all. Whatever he told you is a lie.”

“It can’t be that much of a lie. He asked me for your hand in marriage today.”

“Mother, no,” I said, fighting the tears that were building in my eyes. “Please tell me you didn’t.”

“A woman without a father is nothing. You need to be protected and taken care of.” My mother kept a controlled coolness that made me angrier.

“No,” I said, feeling my world crashing in. I was only fourteen. I wasn’t ready for this.

“The contract is already signed,” my mother said, as if she were buying produce at the market.

“I can’t believe you did this without my permission! I shouldn’t have to marry anyone!” I yelled.

“Anna!” She dropped her food onto her plate. “I am your mother. I don’t need your permission to do anything. I could have you dragged out into the streets and beaten for your disrespect. No one would even question me. Whatever notions you have in your head, you need to get rid of them right now. You have two purposes in life. One is to get married and the other is to make children with your husband. That’s it.”

“If that is to be my lot in life, then why not pick someone better? Why not let me marry someone of my own choosing?”

“Because you will be foolish and marry for love. You are a dreamer, Anna, always with your head in the clouds. I will not let you make my mistakes. Manoel will be a good husband.” Her voice shook as she pressed her fists against the table.

“How do you know? Do you know anything about him at all?” I asked as my eyes betrayed me, letting tears trickle out. Manoel Duarte had a small, run-down shoe repair shop in the center of town. It was a well-known fact that the reason his shop was so badly kept was because all of his profit was spent at the tavern. The tavern owner’s wife liked to joke that Manoel was a gracious benefactor. It was because of his patronage that she was able to acquire so many new dresses. And this was the man my mother expected me to marry?

“You haven’t gotten any other offers, and he promised that he would take good care of you.”

“Yes, because the promises of a drunk are always to be believed.” I stormed out of the house, running as fast as I could. I made it down to the docks, where I grasped my sides, sucking in deep, jagged breaths. My mind raced. I couldn’t believe this was happening. I paced, trying to control my breathing. I looked at the ships rising and falling with the gentle rocking of the ocean. Perhaps I could get on one and sail away to some other land. I took a step toward the harbor. For a moment, I closed my eyes, imagining. I could go somewhere exotic, like France or Africa. I could run away. B

e a merchant, have adventures. Sail the seas. Get out of this horrible town. I could…

I shook my head, wiping away my silly thoughts. Even if I ran away, what would I do when I got there? I raised my chin as I regained control of my breathing. There was only one thing I could do. I turned on my heel and walked home. I was going to get married whether I liked it or not. Because as my mother said, I was nothing without a husband or a father.

Four

August 1835

August 21, 1835, was the day I married Manoel. Gray clouds blanketed the sky above the steeple. The gloomy afternoon mirrored my mood. The night before my wedding my mother slipped into my room and petted my hair. “Don’t be sad,” she said. “This marriage will be a good thing. You have the spirit of men’s longing in your eyes. And that is so dangerous for a girl. It scares me. Soon you will come to see that a marriage will tame you. Keep you safe.” She thought she was making me feel better, but my despair only grew.

I stood in front of a yellowed mirror while my mother fussed with my veil, waiting for the ceremony to begin. I wore a simple dress that had probably been fashionable when my mother was a girl. She’d purchased it from a newly widowed woman after being appalled by my plan to wear the same clothing I wore when cleaning houses. Just to be safe from any bad luck, my mother had the dress blessed by the priest.

“You look so much like your father,” she said, smoothing out a stray wrinkle in my dress. “Such a shame his looks did not translate well to a girl.”

She stopped and met my eyes in the mirror. “Try to be happy today, Anna. You will now be a woman. Your life is finally beginning.” How could it be beginning when I felt like I was dying inside?

Standing at the altar, I looked over my new husband as he said his vows to our priest. Manoel’s hair was slicked back with oil, and a thin trail of sweat rolled down his temple. He was even greasier than usual. How can that happen? I wondered. He was beaming, as if he had just won a hard-fought contest. I said the vows I had practiced like I was supposed to, not giving him the pleasure of a smile.

The Woman in Red

The Woman in Red